2003-01-25 10:47

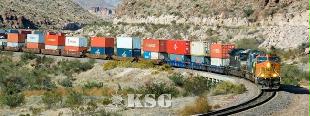

Hub port in Northeast Asia, who takes it?

Which country will take the honored throne of ‘hub port for Northeast Asia’?

As international logistic flows switched over to regional mega-hub ports coming into the 1990s, individual countries are quickly keeping pace with the international logistic trend, announcing plans to become hub ports by building more container wharves and introducing new facilities in their ports.

Especially, Northeast Asia is showing more serious competition than other regions in the world. That is because Northeast Asia is neighboring with China, which has over 10% annual growth, and because it is located on the main trunk routes to Europe and North America. As a matter of fact, the global top 5 container ports in 2002 came from Asia: Hong Kong, Singapore, Busan, Kaohsiung, and Shanghai.

Amongst these ports, Shanghai is regarded as the strongest competitor for a Northeast Asia hub. To solve the shallow water depth and lack of terminal capacities, Shanghai is dredging to deepen the water to 12.5 meters by 2008 and is driving hard forward with the ‘Yangshan project’ to build 52 berths by 2010. As Shanghai is also acutely aware of the importance of facilities acquisition to handle skyrocketing cargoes, it is building five container berths as the first phase of the project scheduled for completion by 2005.

Japan also announced its ‘Super Hub Port’ plan to bring up 3-4 super hubs across the country. The Japanese government would pick the 3-4 super hub ports from amongst its domestic ports and have them lower port dues by 30% and cut off lead-times to 1 day from the current 3-4 days.

The Korea Maritime Institute said that each country in Northeast Asia has been lowering port dues except for Hong Kong in order to attract cargoes and shipping companies. The Port of Kobe has continuously tried to add more facilities, improve stevedoring services and lower terminal charges. Kaohsiung also lowered its port dues to keep pace with Busan. Even Singapore has restricted rises for port dues and stevedoring rates and even offered discounts in order to keep global mega-carriers from leaving its port amongst the severe competition of neighboring ports.

Current Korean port situation

Total port cargoes in Korea rose 886 million tons in 2001, an annual average increase of 7.9% from 413 million tons in 1991. However, container cargoes posted a 13.7% annual average growth during the 10 years since 1991, recording 9.99 million TEUs in 2001. This encouraging figure was attributed to snowballing transit cargoes in the same period, marking a massive 36% annual growth. Transhipment cargoes are usually regarded as producing an additional 200 dollars per TEU in terms of stevedoring rates, port entry fees, terminal fees and shuttle fees. In 2000, handling 2.45 million TEUs of transit cargoes, Busan posted 300 million dollars income (roughly equivalent to the amount earned by exporting 900 thousand cars).

The problem is that Korea has showed facilities shortages in the port as port investment has failed to catch up with snowballing cargo growth. In order to handle fast growing cargoes, port facilities needed to see a 9.1% annual increase during 20 years since 1981. However, stevedoring capacity only grew by 8.6% during the same period.

KMI researchers said that the shortage of port facilities was caused mainly from lack of government investment. Port investments in terms of GDP (Gross Domestic Products) stood at 0.22% in Korea, while in Japan it was 0.39% and in Taiwan 0.42%. Also, the legal system still contains elements unfavorable to port investment. Additional port investment is hardly helped by the ‘special traffic tax’ to be charged by the end of 2003. With the difficulty in getting government finance, drawing private capital is the only alternative. In Korea, private capital usually comes from construction companies. Also, earlier low cargo estimates from before 1995 led to failures to build enough facilities to keep up with the actual workload. In theory, the plan in 1996 set the expected cargoes to 13.9 million TEUs in 2006 and 19.2 million TEUs in 2011. However, as actual economy growth and cargo expectations turned out to exceed the predictions, the government revised the National Port Plan in December 2001 to add more container wharves. In the plan, the government focused on finding ways to improve international port competitiveness and secure more port facilities. The revised plan called for container terminals to have 84 new berths by 2011.

At first, in order to solve the berth shortage, three berths constructed with private capital in Busan New Port would be opened between January 2006 and September 2007. Also, 12 berths in the southern container terminal would be built by the government to keep the port development plan on schedule. By 2011, Busan New Port will have 30 berths to accommodate 8.1 million TEUs of cargoes, at a cost of 7.99 trillion won. Gwangyang also experienced container cargo increases and will have 33 berths by 2011 boasting an annual capacity of 9.32 million TEU.

To help logistic flow in the metropolitan area, Pyoungtaek and Inchon were chosen for investment in the port plan.

In the mean time, foreign investors rushed into Korean ports. In early 2002, Hyundai Merchant Marine sold terminals, including Jasungdae, Gamman and Gwangyang terminal, to Hutchison Port Holdings for 215 million dollars (282.5 billion won) in order to solve liquidity problems at HMM. CSXWT joined in Busan New Port operation and management by purchasing a 25% share of the Busan New Port Corporation. CSXWT will operate 6 berths for 30 years. PSA is also waiting to operate its terminals in Inchon Southern Port. Inchon Container Terminal, a joint venture company of PSA and the Samsung Corporation, is developing berths, and has scheduled the opening of one berth by April 2004. As a mega carrier, Evergreen invested in the Dongbu Pusan Container Terminal (DPCT) in 2002.

As international logistic flows switched over to regional mega-hub ports coming into the 1990s, individual countries are quickly keeping pace with the international logistic trend, announcing plans to become hub ports by building more container wharves and introducing new facilities in their ports.

Especially, Northeast Asia is showing more serious competition than other regions in the world. That is because Northeast Asia is neighboring with China, which has over 10% annual growth, and because it is located on the main trunk routes to Europe and North America. As a matter of fact, the global top 5 container ports in 2002 came from Asia: Hong Kong, Singapore, Busan, Kaohsiung, and Shanghai.

Amongst these ports, Shanghai is regarded as the strongest competitor for a Northeast Asia hub. To solve the shallow water depth and lack of terminal capacities, Shanghai is dredging to deepen the water to 12.5 meters by 2008 and is driving hard forward with the ‘Yangshan project’ to build 52 berths by 2010. As Shanghai is also acutely aware of the importance of facilities acquisition to handle skyrocketing cargoes, it is building five container berths as the first phase of the project scheduled for completion by 2005.

Japan also announced its ‘Super Hub Port’ plan to bring up 3-4 super hubs across the country. The Japanese government would pick the 3-4 super hub ports from amongst its domestic ports and have them lower port dues by 30% and cut off lead-times to 1 day from the current 3-4 days.

The Korea Maritime Institute said that each country in Northeast Asia has been lowering port dues except for Hong Kong in order to attract cargoes and shipping companies. The Port of Kobe has continuously tried to add more facilities, improve stevedoring services and lower terminal charges. Kaohsiung also lowered its port dues to keep pace with Busan. Even Singapore has restricted rises for port dues and stevedoring rates and even offered discounts in order to keep global mega-carriers from leaving its port amongst the severe competition of neighboring ports.

Current Korean port situation

Total port cargoes in Korea rose 886 million tons in 2001, an annual average increase of 7.9% from 413 million tons in 1991. However, container cargoes posted a 13.7% annual average growth during the 10 years since 1991, recording 9.99 million TEUs in 2001. This encouraging figure was attributed to snowballing transit cargoes in the same period, marking a massive 36% annual growth. Transhipment cargoes are usually regarded as producing an additional 200 dollars per TEU in terms of stevedoring rates, port entry fees, terminal fees and shuttle fees. In 2000, handling 2.45 million TEUs of transit cargoes, Busan posted 300 million dollars income (roughly equivalent to the amount earned by exporting 900 thousand cars).

The problem is that Korea has showed facilities shortages in the port as port investment has failed to catch up with snowballing cargo growth. In order to handle fast growing cargoes, port facilities needed to see a 9.1% annual increase during 20 years since 1981. However, stevedoring capacity only grew by 8.6% during the same period.

KMI researchers said that the shortage of port facilities was caused mainly from lack of government investment. Port investments in terms of GDP (Gross Domestic Products) stood at 0.22% in Korea, while in Japan it was 0.39% and in Taiwan 0.42%. Also, the legal system still contains elements unfavorable to port investment. Additional port investment is hardly helped by the ‘special traffic tax’ to be charged by the end of 2003. With the difficulty in getting government finance, drawing private capital is the only alternative. In Korea, private capital usually comes from construction companies. Also, earlier low cargo estimates from before 1995 led to failures to build enough facilities to keep up with the actual workload. In theory, the plan in 1996 set the expected cargoes to 13.9 million TEUs in 2006 and 19.2 million TEUs in 2011. However, as actual economy growth and cargo expectations turned out to exceed the predictions, the government revised the National Port Plan in December 2001 to add more container wharves. In the plan, the government focused on finding ways to improve international port competitiveness and secure more port facilities. The revised plan called for container terminals to have 84 new berths by 2011.

At first, in order to solve the berth shortage, three berths constructed with private capital in Busan New Port would be opened between January 2006 and September 2007. Also, 12 berths in the southern container terminal would be built by the government to keep the port development plan on schedule. By 2011, Busan New Port will have 30 berths to accommodate 8.1 million TEUs of cargoes, at a cost of 7.99 trillion won. Gwangyang also experienced container cargo increases and will have 33 berths by 2011 boasting an annual capacity of 9.32 million TEU.

To help logistic flow in the metropolitan area, Pyoungtaek and Inchon were chosen for investment in the port plan.

In the mean time, foreign investors rushed into Korean ports. In early 2002, Hyundai Merchant Marine sold terminals, including Jasungdae, Gamman and Gwangyang terminal, to Hutchison Port Holdings for 215 million dollars (282.5 billion won) in order to solve liquidity problems at HMM. CSXWT joined in Busan New Port operation and management by purchasing a 25% share of the Busan New Port Corporation. CSXWT will operate 6 berths for 30 years. PSA is also waiting to operate its terminals in Inchon Southern Port. Inchon Container Terminal, a joint venture company of PSA and the Samsung Corporation, is developing berths, and has scheduled the opening of one berth by April 2004. As a mega carrier, Evergreen invested in the Dongbu Pusan Container Terminal (DPCT) in 2002.

많이 본 기사

- “연평균 12%씩 공급 증가” 원양항로 불확실성 고조한화엔진, 노르웨이 전기추진기업 인수…친환경선박사업 강화獨 하파크로이트, 4500TEU등 중소 컨선 22척 도입한국선급, 창립 65년만에 등록톤수 9천만t 돌파MSC그룹, 방글라데시 내륙터미널 운영권 확보북미항로/ ‘대중제재 여파’ 中 물동량 감소…베·印 역대최대그린글로브라인, 2025 연례회의 개최…업무 현황 점검중남미항로/ 수요 증가에 선사들 서비스 개설 잇따라호주항로/ 물동량 증가에도 운임 약세 표면화…17개월來 최저치아시아나IDT, ‘첨단안전산업인의 밤’서 장관상·원장상 동시 수상

- 구주항로/ 선사들 공급 축소·운임 인상으로 시황회복 안간힘아프리카항로/ 하반기 운임 약세로 고전MSC–스리랑카항만청, 콜롬보항 터미널협정 체결인사/ 인천항만공사中 헝리조선소, 올해 100척 수주 달성…11월이후 34척 계약팬스타그룹, 연말연시 맞아 해돋이·불꽃쇼등 크루즈 이벤트 진행BPA, 교육기부 우수기관 인증·부산교육메세나탑 수상판례/ 허위 송장을 요구했는데도 면책이 된 이유인사/ 해양수산부“국감문제 해결안돼 마음 무거워” 한국선급 이형철 회장 퇴임

스케줄 많이 검색한 항구

0/250

확인